|

Kentucky Confederate Home in Pewee Valley, Kentucky

|

|

Originally named Villa Ridge Inn, it originally opened as a luxury summer resort for Louisville businessmen and their families, was an impressive three-story structure that boasted the majestic architecture of the period. The Inn was closed after a couple of seasons. The building later served as a College for Young Ladies before being purchased by the state of Kentucky to provide a home for Confederate veterans in 1902. The idea for a Confederate Home was conceived by native Kentuckian, Bennett H. Young. A businessman and former Confederate officer, Young noticed the need for a shelter for aging Civil War veterans who often suffered from war-related illnesses and were unable to provide for themselves. The Confederate Home opened its doors to the first occupant in November 1902. Located on the land adjacent to the old Presbyterian Church close to the cemetery off Hwy. 146. The following was provided to Sandi Gorin by Mr. Robert Fortunato who earlier gave his permission to share. Sandi Gorin has given her permission to share also.

“For most of the men in the Confederate soldiers’ homes, their military service was forty years behind them. But when they entered the home, they voluntarily returned to a quasi-military of life. At the Kentucky Confederate Home they started at 6 a.m. with a cannon shot from a field artillery piece on the front lawn, and a color guard would raise the U. S. and Confederate flags over the building. The men would fall in for roll call and uniform inspection, then march off to breakfast. (Breakfast might include sliced ham, gravy, fried potatoes, biscuits, fruit preserves and coffee.) If the weather was good, they might stroll the grounds after breakfast, or find a chair on one of the galleries, but the rules prohibited them from leaving the Home’s grounds without the commandant’s permission and a written furlough slip. (Some of the homes required men to perform several hours of “productive work” every day – farming, building repair, painting – unless they were on sick call.) Dinner, served at midday, was the heaviest meal of the day, more suited to a farmer than a sedentary seventy-year-old. Afterwards, they might nap or pursue a hobby (like whittling, gardening or photography). There were always games of checkers going on. The special days, though, were when they had some kind of entertainment. Ladies from the United Daughters of the Confederacy would often organize parties or recitals for the old vets. Religious services were held on Sundays and Wednesday night, usually conducted by a local preacher or traveling evangelist. The real treat was when touring vaudeville groups would stop in at the homes to perform for the old men. By the 1920’s, most homes had movie projectors, and local theaters would loan out prints of popular movies. Misbehavior wasn’t tolerated, and most homes had a procedure much like a court-martial that could lead to confinement or discharge from the home. The Confederate soldiers’ home men lived up to standards never required of them in civilian life. Some thrived in the environment, others resisted to the point of expulsion.” In 1906, a complaint was filed with the State about the living conditions, the food, the lodging and the medical care at the Confederate Home in Pewee Valley by a supposed veteran who had begged for temporary lodging there. It was thoroughly inspected and some of the findings included: It was found that the charges were frivolous … The physicians in charge were found that the infirmary was “the best managed institution of its kind they had ever seen”. The committee found that “all rooms were in a most satisfactory condition; the beds were comfortable and clean, and well kept in every respect; the bath rooms and water closets and all the plumbing and sanitary arrangements were found to be without any objections whatever.” In examining the food provided, the committee noted that the food was of high quality, such as is furnished institutions like the Galt House, Louisville Hotel or Pendennis Club.” Many of the old veterans are of course buried in the cemetery as shown by previous tips. Many were brought home for burial. The requirements for occupancy of the home included that the applicant be an honorably discharged Confederate veteran, a resident of Kentucky for six months prior, of sound mind and free of addiction to alcohol. Applications came from across the state, and soon the home became a sanctuary for as many as 350 aging and disabled veterans at a time.

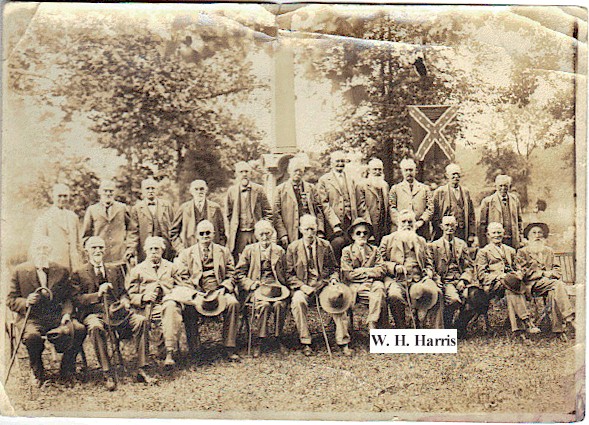

Photo Contributed By: John Bennetsen Great-Great Grandson of W. H. Harris. More photos and information here. On March 25, 1920, a fire destroyed a large section of the home. Fortunately, no lives were lost due to the tragedy, but the main building, the laundry and one ward of the infirmary were ruined. What was left of the property was sufficient to house the remaining inmates, whose numbers had dwindled over the years and the remainder of the buildings have since been torn down. By the mid-1930's only five inmates remained. After 32 years of operation, the decision was made by the state to close the home in July 1934. The five remaining inmates were transferred to the Pewee Valley Sanatorium The only parts of the Confederate Home remaining in Pewee Valley include the original sign at the front gate (shown in the 1936 Herald-Post photo to the right), now at the entrance to the Confederate portion of the Pewee Valley Cemetery, and the remnants of the old walkway that led from the home to the railroad tracks, marked by a small sign placed there by the 21st Century Confederate Legion. Pewee Valley Confederate Cemetery is the site of the old Kentucky Confederate Home. The cemetery is not only on the National Register of Historic Places, but an individual monument within it, the Confederate Memorial in Pewee Valley, is separately on it as part of the Civil War Monuments of Kentucky MPS. It is the only cemetery for Confederate veterans, 313 in total, that is an official state burying ground in Kentucky. |